10 Case-control study

10.1 Design and why do Case-control study?

Difference between Cohort and Case-control study

Cohort study: We have exposure data on all those in the study population who develop the outcome, and all those who do not.

Case-control study: we collect exposure data on all cases and controls. However, the controls are only a sub-set of the study population of “non-cases” rather than all non-cases in the study population.

Design

In a case-control study, we start by identifying individuals with the outcome of interest (cases), and individuals without this outcome (controls). We then obtain information about one or more previous exposures from cases and controls, and compare the two groups to see if each exposure is significantly more (or less) frequent in cases than in controls.

Why do case-control study

useful for rare outcomes: because the starting point is the identification of people with the outcome in question.

past exposures and outcomes are measured at the same time, so these studies can be done quickly, without the need to wait for a disease to develop or an event to occur.

10.2 Main steps in conducting a Cohort study

Step 1: Defining the study question

Step 2: Defining the target population

Step 3: Selecting the cases

The cases must be a clear defined group with 3 properties:

a. Case definition refer to Measure of Occurrence section.

b. Source

We must define the population from which the cases are drawn, because the controls will need to be drawn from the same population. The cases could be:

all patients who fulfil the case definition who attend a specific hospital within a specified time period

all patients within a specified population who have the outcome in question within a specified time period. We might need to use multiple sources of data to identify all such patients.

We need to clarify the case group represent all cases in the target population or just a subgroup of cases. If we are studying a common disease, we may not want to study all cases within a given population. If we decide to study a sample of cases, then this sample should be a representative sample of all possible cases who fulfil the case definition within the specified population.

For some diseases with a spectrum of severity, patients from a hospital population are likely to have more severe disease than those from a primary care setting.

c. Incident or prevalent cases

If we use incident cases, we will identify risk factors associated with the onset of the disease. However if we use prevalent cases, we will under-represent cases with more rapidly progressive disease who die rapidly after diagnosis, and are therefore less likely to be included in the study. Thus if we use prevalent cases in a case-control study, any risk factors identified as associated with the disease may be not just those associated with the development of the disease, but could also be those associated with longer survival with the disease.

Step 4: Selecting appropriate controls

Controls must be representative of the population that produced the cases, but must not have the outcome in question. We can consider how to select the cases with 4 questions:

what should be the source of controls?

1, If the cases are a population based sample of incidences, population based controls would be appropriate (a random sample of the same population without the outcome of interest)

Data sources could be:

lists of people registered with a primary care physician

lists of people cared for by a village health worker

census data

Note: all of these data courses have some limitations, 1 source is unlikely to provide a complete accurate information.

2, If cases are derived from a health care facility, many studies use controls from the same health facility. Because these controls are easy to recruit, more likely to participate with less losses of follow up, less risk of recall bias as they have an illness. However, these controls may not be representative of the population which produced the cases and selection bias maybe introduced.

should there be more than one group of controls?

Ideally we should have 1 control group but sometimes we need more than one.

how many controls per case?

No more than 4 controls per cases.

should the controls be matched to the case?

We make our study more efficient if we match on a few simple variables (such as age and sex). However, if we try to match on many variables it becomes increasingly difficult to find appropriate matched controls for each case.

Matching types:

Individual matching: a control is selected match to a cases on a few desired variables.

Group matching: Instead of matching each individual, we select control group match to the case group. e.g. case group contains 60% male, and mean age 25, we should recruit a control group with similar sex and age distribution. This usually requires that all the cases be chosen before we start to select controls

Matching does not remove the confounding effect. Matched studies require an analysis that takes the matching into account.

We should only match for an exposure if the relationship between that exposure and the outcome is already understood.

Matching on an intermediate variable results an underestimate of the association between the exposure and outcome of interest.

Matching on a variable that is associated with the exposure of interest but not with the outcome can reduce the efficiency of the study and weaken our ability to detect an association.

Nested case-control study

Nested case-control study is carried out within a cohort study with 2 advantages:

both cases and controls are derived from the same population. Controls are representative of non-cases population, thus reduce selection bias.

exposure is identified before outcome occurred, reduce information bias and have less risk of reverse causality.

More than 1 nested case-control study can be carried out within a single cohort study.

Step 5: Measuring exposure

Possible source of exposure data:

interview of participants

interview of a person close to the study participant

medical records

occupational records

biological samples

We need to consider the latency time as this determines the period we should collect exposure information.

we must be sure that the method used to gather information is as accurate for cases as it is for controls:

use objective records rather than subjective measures to measure exposure status when possible, providing they are accurate

use measures of exposure taken before the outcome occurred (which are therefore less likely to be biased by outcome status) when possible.

if there are no pre-existing sources of exposure data, and the measurement of exposure requires a subjective judgement by the investigator, make the investigator “blind” to the outcome status of the participant.

Step 6: Analysing the data

we compare the prevalence of exposure among cases with that among controls.

we usually use odds to express the frequency of the exposure among the groups of cases and controls. We compare the odds of exposure among cases and controls by calculating the ratio of the odds of exposure.

a) Incident cases

there are three strategies for the sampling of controls and the measures of effect vary dependent on the strategy.

If we sample a control from the population at the same time a case is identified, the exposure odds ratio estimates the rate ratio.

If we sample our controls from the source population at the beginning of identification of incident cases the exposure odds ratio estimates the risk ratio.

If we sample our controls from the source population at the end of identification of cases the exposure odds ratio estimates the odds ratio (of disease).

In the situation of a rare disease the exposure odds ratio for all three strategies of sampling estimates the risk ratio, rate ratio and odds ratio of disease. This is because when the disease is rare in the study population, the odds ratio, risk ratio and rate ratio are all very similar numerically.

b) Prevalent cases

If we select controls at the time of identification of cases (prevalent controls), the odds ratio estimates the prevalence odds ratio.

Under certain assumptions, most importantly that the duration of the disease is not associated with exposure, the prevalence odds ratio estimates the rate ratio. If the disease is rare the prevalence odds ratio estimates the prevalence ratio.

Note:

There may be more than one level of exposure, in which case we calculate an odds ratio for each stratum compared to the baseline. The baseline is often the unexposed group (or lowest level of exposure) but a different stratum may be chosen as a baseline, particularly if there are few cases in the unexposed group (which would make the estimate of disease occurrence in that stratum unreliable.

An individually matched design requires a matched analysis, and the odds ratio is calculated differently using ‘discordant pairs’. The analysis of individually matched data is discussed in the module Statistics for Epidemiology (EPM102).

Group-matched (or frequency-matched) studies do not need a ‘discordant pairs’ analysis. However, we should still treat the matched variable as a potential confounder, and adjust for it in the normal way through stratification or regression modelling.

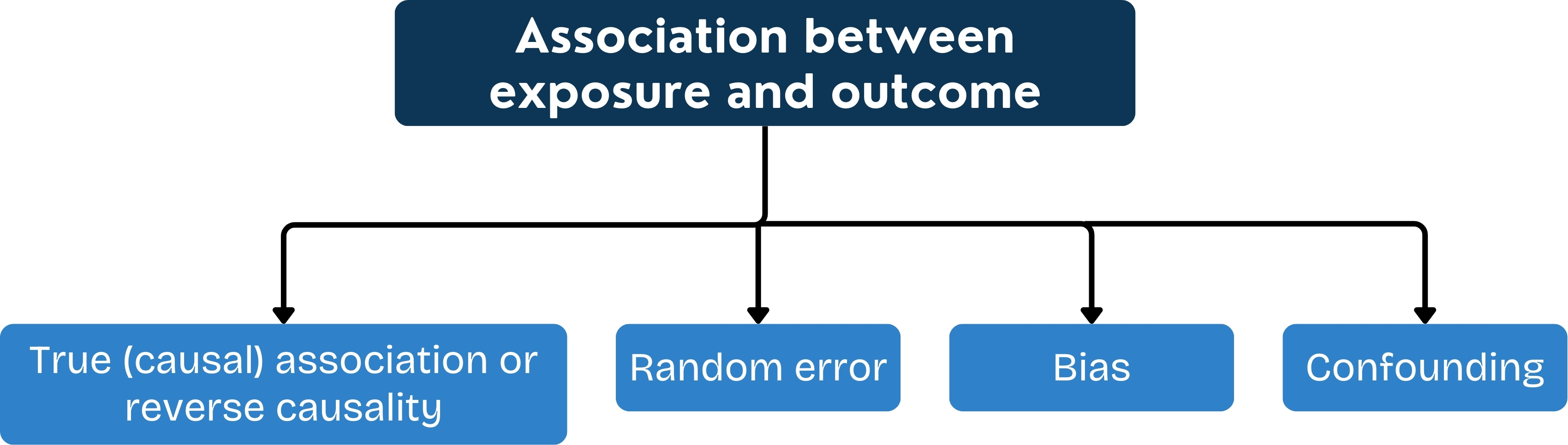

Step 7: Interpreting results

Bias

The potential sources of bias in case-control studies are:

selection bias in selecting cases and controls

information bias in obtaining data on exposure

Controls are derived from hospitals have some advantages as above. However, they may not be representative of the population that produced the cases.

Confounding

Refer to Confounders and Effect Modification section for more information on confounding.

Methods for controlling confounding include:

at the design stage using restriction and matching

in the analysis using stratification and regression modelling

Random error

Measurement error may result in misclassification of exposure or outcome and lead to inaccurate estimate.

Reverse causality: As the exposure is measured after the outcome has occurred, it is possible that the exposure have been influenced by the outcome. It is important to define the exposure period of interest in case-control studies. For diseases with long latent periods (for example, lung cancer), this may be many years prior to the onset of disease. Where the latent period is short (for example, diarrhoeal disease), the relevant exposure period may be only days before the outcome occurs.

Exposure status may also be influenced by the early stages of a chronic disease, before the outcome as defined in the case definition has occurred.

10.3 Strength and Weakness

Strength

can be carried out rapidly and relatively cheaply (compared to cohort studies)

are useful for studying rare diseases

can be used to study diseases with long periods of time between the exposure and outcome

can study multiple exposures for a single outcome

Weakness

are prone to selection bias, particularly in the selection of controls. This is the main week point of case-control study as controls are selected sample of non-cases instead of all the non-cases in the reference population

are prone to information bias, because exposure status is determined after the outcome has occurred

cannot establish the sequence of events: the exposure may be a consequence rather than a cause of the outcome (reverse causality)

are not suitable for studying rare exposures (except in nested case-control studies)

cannot usually be used to estimate disease incidence or prevalence